Railweb Reports

Polish intermodal rail freight, Europe and the Silk Road

Posted by George Raymond on January 21, 2021

For decades, rail freight has been losing market share in the EU. In recent years, however, rail-based intermodal services have been growing. Both these trends are particularly pronounced in Poland. EU policies and its Green Deal are upgrading infrastructure. What further intermodal growth will result in Poland by 2030?

At the same time, China is subsidising intermodal Silk Road services to and through Poland. Most Silk Road traffic is westbound Chinese exports. Can more eastbound EU exports bolster the Silk Road’s economic and political sustainability?

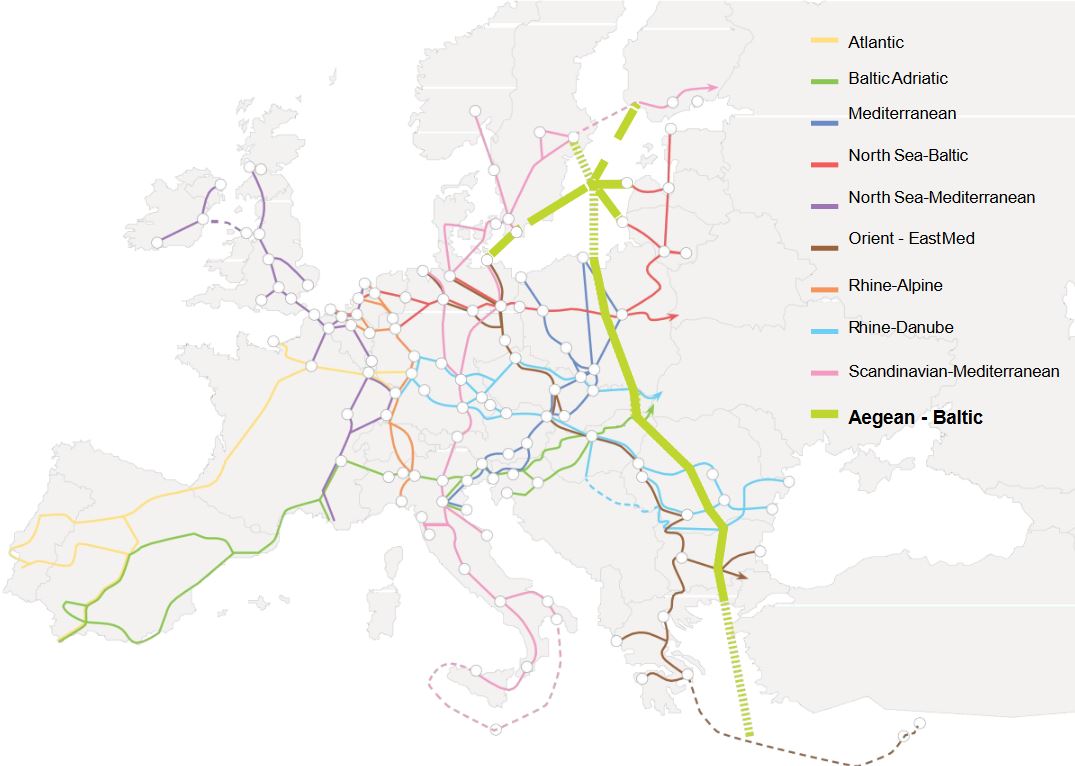

In any case, intermodal growth in Poland will require longer and faster trains, easier border crossings, attractive hubs and ports, ways to load non-cranable truck trailers, and robust operator networks. And digitalisation. The North Sea – Baltic, Rail Baltica, GUAM and Aegean-Baltic corridors can also help.

These were some of the discussions at a September 2020 conference in Poznań.

At the venue of the Poznań conference on rail freight of 1-2 September 2020. The conference was also online. Rail Freight Summit video feed.

At the venue of the Poznań conference on rail freight of 1-2 September 2020. The conference was also online. Rail Freight Summit video feed.

Overview

Local spellings and OpenRailwayMap

The very helpful website OpenRailwayMap shows details of the sites and routes mentioned here. Unlike search engines, however, ORM finds places like Sławków and Małaszewicze only if you use the local spelling. So we’ve tried to use local spellings here too.

Polish modal split: reversing the trend?

Conference speakers addressed rail’s dropping market share in Poland, the rise of intermodal – which Europe also calls combined transport – growth scenarios to 2030 and truck competition.

Rail freight down, but intermodal up

Rail’s tonne/km market share in Poland plummeted from 42% in 2000 to 19% in 2010 to 12% in 2019. This was pointed out by Jana Pieriegud of the Department of Infrastructure and Mobility Studies at the Warsaw School of Economics. But, she said, container transport by rail has been bucking this trend. Between 2004 and 2019, it grew faster in Poland than in Germany, Czechia or Slovakia, from 300,000 to 2.2 million 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs). Michal Jaworski of the Polish Office for Railway Transport said that in the first half of 2020, rail TEUs in Poland rose a further 16.2% year-on-year. This was partly due to European demand for Chinese personal protection equipment (PPE) and the pandemic’s disruption of air and ocean freight.

Paths to regaining market share

The EU wants rail freight and inland waterways to claim 30% of the European freight market by 2030. This seems over-ambitious for Poland. Assuming that annual GNP grows by 2.0% and tonne-km 3.8% a year, Ms Pieriegud saw three scenarios for Polish rail freight to 2030:

- Volume stagnant, share down: If rail retains the annual volume of about 55 billion tonne-km it has had since 2000, by 2030 its market share will shrink to 9%.

- Volume up, share steady: If rail is to maintain its current market share of 12%, it must increase its volume by 60% to 80 billion tonne-km, a volume comparable to 1990. It must therefore regain in 10 years what it lost in 30.

- Volume and share up: If rail’s market share is to increase from 12% to 20% by 2030, it must multiply its volume by 2.5 to 138 billion tonne/km, which was roughly its 1978 level. This would exceed Germany’s volume today. [George Raymond: Most of this would be expected to come from intermodal].

A DB Cargo Polska train passes Kudrowiec Pond at Chełm Śląski, about 70 km northeast of its departure point, Petrovice u Karviné, just inside Czechia, on 5 July 2018. It is bound for Małaszewicze. Photo © Derk Luijt

Ms Pieriegud asked whether existing Poland lines with mixed passenger and freight traffic could absorb this. A shift from road to rail requires a totally new approach for freight transport development in Poland, she said.

Truck competition

Roland Verbraak of operator GVT Intermodal pointed out that an inherent advantage of intermodal rail transport over truck transport is that a train can change drivers and continue almost immediately, whereas a truck must generally wait for its driver to rest or sleep. Ms Pieriegud said that rising labour costs for trucking will favour rail. But Mr Verbraak said that the pandemic has lowered both fuel prices and truck transport prices in Europe. And the Netherlands now allows 32-metre trucks.

Infrastructure investments in Poland

Despite investing billions of euros in rail infrastructure, speakers said, Poland’s progress toward longer and faster trains is slow. Operators suggested that Poland motivate its state-owned rail infrastructure operator by dropping fees for access to lines that limit train length and speed and by raising fees for lines that allow longer and faster trains.

Recent investments

Since 2000, Ms Pieriegud said, Poland has received €18 billion for existing railway lines. This has brought some improvements. Between 2004 and 2019, the part of the Polish rail network that can bear at least 22.5 tonnes per axle rose from 39% to 60%. But the timetable speeds of freight trains have risen only from 24 to 25 km/h.

The long walk to 740 metres

Intermodal operators want to run 740-metre trains, the European objective. Mr Verbraak of GVT Intermodal said that 64% of Europe’s intermodal trains are 600 metres or less and only 11% are 700 to 835 metres long. Izabela Kaczmarzyk of T-Plan Consultants said that only 51% of Polish core freight lines can move 740-metre trains. As elsewhere, the problem is not just short holding tracks, but also traffic bottlenecks, especially at peak hours. An audience member pointed out that holding tracks must be longer than the trains they hold to provide a safety margin if a train overruns a stop signal. Dariusz Stefanski of PCC Intermodal called 740-metre trains the intermodal industry’s dream and 600 metres Poland’s standard. [GR: Short holding tracks along a route are a harder constraint than short tracks in a terminal, where wagons from several short tracks can form a longer train.]

In central Poland, about 73 km north of Łódź and midway between Poznań and Warsaw, PCC Intermodal’s Kutno terminal and its four 700-metre loading tracks. Photos summer 2018, © PCC Intermodal

Ms Kaczmarzyk said that given a limited number of holding tracks admitting 740-metre trains, better traffic organisation can improve a line’s capacity for such trains. But that the railway infrastructure managers (IMs) lack a common policy, and this exacerbates capacity problems at borders. She said that the de facto priority of passenger trains limits operation of 740-metre trains on Belgian and German rail infrastructure.

Slowing down to accelerate

One problem is that for the moment, works that aim to speed trains up are slowing them down. Dariusz Stefanski of PCC complained of closures and other difficulties related to the “endless” modernisation of railway lines in Poland and elsewhere. David Aloia of Hupac said that 100 trains had recently been stuck at the Polish-Beluras border at Brest/Małaszewicze because Polish infrastructure works were not coordinated with actors to the east along the routes from China.

Missing incentives

Mr Stefanski said that the state-owned rail infrastructure operators (known in Europe as infrastructure managers) have little incentive to fix their infrastructure. He said that IMs claim everything is being improved, but he sees no light in the tunnel, especially at border points. He asked how IMs can be motivated to treat operators as customers. He also saw a lack of understanding or proper support in the Polish government, where no one is responsible for intermodal transport.

Should track access fees reflect train speed and length?

To provide the rail infrastructure operators of Poland – and other EU countries – with an incentive for improvements, intermodal operators at the conference said that track fees should rise with train speed and length.

Mr Stefanski said that given the low commercial speed of freight trains – less than 30 km/h – and the significantly lower access fees for road infrastructure, access fees for Polish railway infrastructure are too high. He suggested that rail access fees vary with speed, as they do on roads. Routes whose commercial speed exceeds 70 km/h should charge higher, premium access fees. Routes allowing 40-50 km/h should command lower fees and rail infrastructure limited to 40 km/h should be free. Mr Stefanski said this would motivate the Polish infrastructure manager, who today collects the same access fees no matter how slow trains are. Similarly, Mr Verbraak of GVT Intermodal proposed that track access fees rise with allowable train length.

The Silk Road boom

The conference examined the Silk Road boom, including the destinations and origins of trade in Poland, the challenge and importance of filling eastbound trains, modal shift opportunities between Poland and the Netherlands, forecasting traffic to evaluate investments, and the factors affecting future Silk Road traffic. First among these are the Chinese subsidies.

Trade destinations and origins

Ms Pieriegud of the Warsaw School of Economics said that in 2019, the top destinations of Poland’s €238 billion in exports were Germany (28%) followed by Czechia, the UK, France and Italy. Import volume was almost identical, at €237 billion. 22% came from Germany, but the next four origin countries were China (12%), Russia (6%), Italy (5%) and the Netherlands (4%).

Mr Jaworski of the Polish Office for Railway Transport said that of the 5200 intermodal trains that ran in Poland in 2019, 61% carried containers moving by rail from or to Asia. Most moved via Brest/Małaszewicze on the Poland-Belarus border. Some 27% of these containers started or ended their journey in Poland and 73% moved to or from countries further west.

[George Raymond: The unprecedented circumstances of 2020 boosted Silk Road rail freight. The pandemic disrupted both air and ocean transport, cutting capacity and raising prices. And demand for Chinese PPE goods was high. As a result, about 50% more containers moved by rail from China to Europe in 2020 compared to 2019.]

On the morning of 28 June 2019, diesels of the company BTK Karpiel hauling containers from Brzesko to the port of Gdynia navigate a cut at Wręczyca Wielka, just south of Kłobuck in southern Poland. Photo © Martin Gáděk

Mr Jaworski said that Silk Road TEUs transiting on rail at Polish border terminals are expected to have grown 16.3% a year from 2016 to 2027 to reach 742,000 TEUs in 2027. At the same time, TEUs transiting at Polish seaports are expected to have grown 12.4% a year from 2017 to 2028 to reach 8.6 million TEUs in 2028. At this rate, by 2028 a tenth of TEUs entering or leaving Poland will be on Silk Road rail routes.

Filling eastbound trains

Adriaan Roest Crollius of Panteia has been studying potential eastbound Silk Road traffic. His focus has been on Dutch exports. Westbound traffic currently dominates on the Silk Road; eastbound traffic is roughly 30% lower. Filling all eastbound trains with full containers would make Silk Road rail services more sustainable by reducing the need for Chinese subsidies. They currently cover about half of the cost of Silk Road services. To develop such traffic, Mr Crollius said, actors must do more to share data and make enough containers and rolling stock available. Panteia is now involved in research on the Silk Road’s political and economic consequences for Europe.

Modal shift opportunities between Poland and the Netherlands

Between 2015 and 2018, Mr Crollius said, rail imports from China to the Netherlands grew from almost zero to roughly 50 million tonnes. He said that the Polish-Belarus border – essentially Brest/Małaszewicze – is a bottleneck for this traffic and thus a focal point. An audience member said that bottlenecks at Małaszewicze cause some westbound containers arriving there to continue to their final European destinations by road. Mr Crollius has been helping the Polish and Dutch governments shift freight from trucks to trains between their countries.

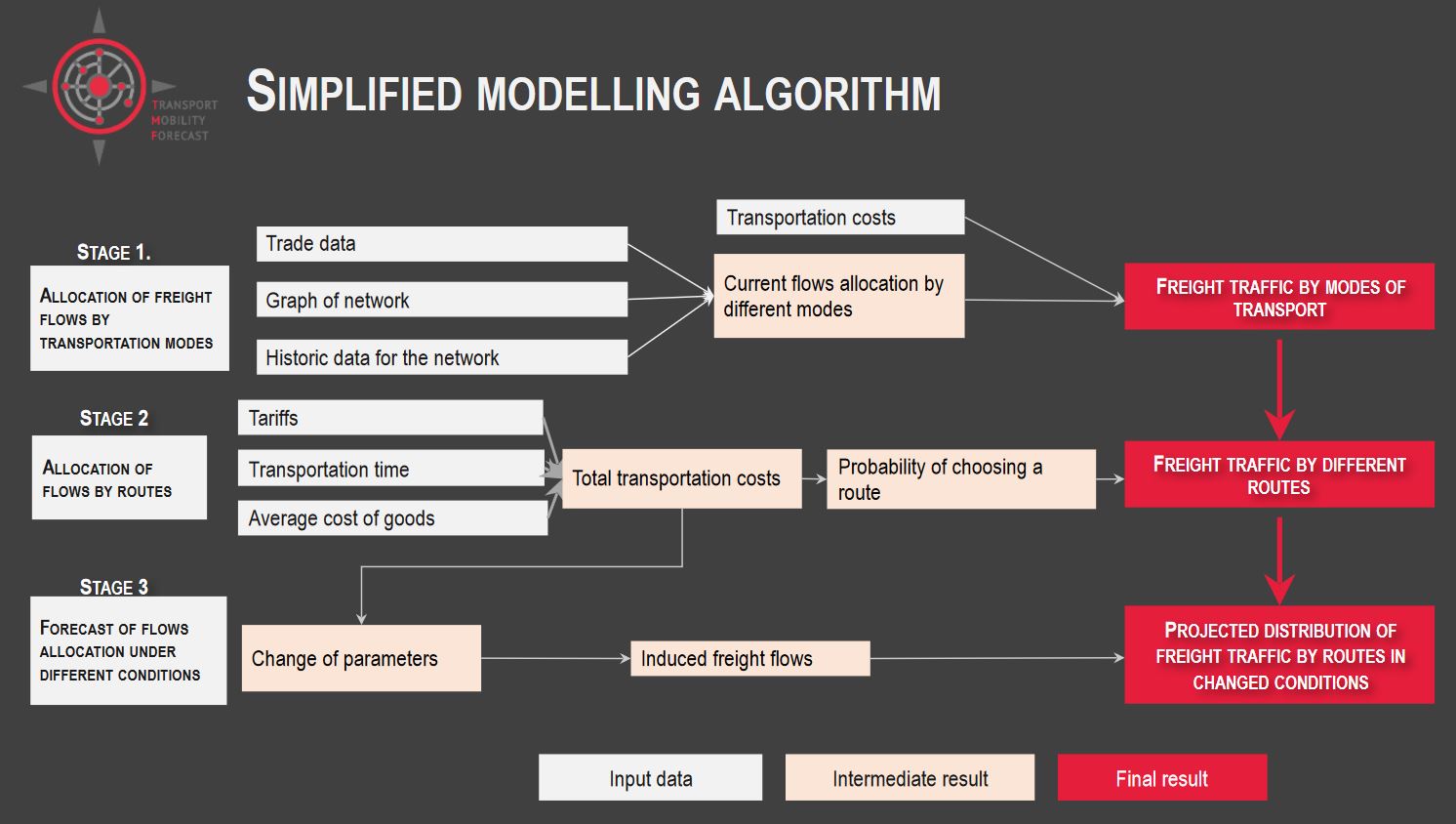

Forecasting traffic to evaluate investments

Ekaterina Kozyreva is president of Moscow-and-Paris-based IED International. She presented factors influencing Silk Road development. Starting from the premise that moving freight by rail makes the world economy more sustainable, she said, the European Green Deal will need to evaluate rail projects to set priorities. This requires a macro-economic outlook because changes in international trade will affect rail traffic flows.

Having been pulled by a diesel locomotive out of PCC Intermodal’s Brzeg Dolny terminal in western Poland, this train is now leaving town behind one of the company’s own electrics in summer 2018. Photo © PCC Intermodal

But a larger determinant of Silk Road traffic may be micro-economic changes in railway infrastructure and services, she said. First among these is future changes in Chinese subsidies. Other factors include better reliability, interoperability, resilience and digitalisation of rail services. Coordinated strategies and marketing initiatives will also affect Silk Road traffic.

Against this background, decision-makers need to evaluate investment projects that may improve rail services, attract volumes from other modes, and even induce flows that would not have existed otherwise. IEC’s traffic projections for specific rail routes are based on scenarios about macroeconomic conditions, aggregate trade between country pairs, transport networks, alternate routes, costs and prices, and induced flows.

IED’s approach to modelling and forecasting Silk Road rail freight flows. IED

IED’s approach to modelling and forecasting Silk Road rail freight flows. IED

IED’s analysis proceeds in three stages: allocation of freight flows to nodes, allocation of flows to routes, and forecast of flow changes under different conditions. IED used this approach in a joint study with the International Union of Railways (UIC) released just before the pandemic.

On the Silk Road, subsidies will be decisive

Further growth of Silk Road rail traffic will depend on infrastructure investments. Evaluating such projects requires forecasting volumes, but these will chiefly depend on Chinese subsidies. Starting from the 2018 baseline of 345 million loaded TEUs and expected growth in international trade, the IED study forecast Silk Road traffic for 2030 under two subsidy scenarios.

| Scenario: level of Chinese subsidy (customers pay the rest) | Projected growth of Silk Road traffic, 2018-2030 | Projected Silk Road TEUs in 2030 |

| 50% (current) | 6.32 times | 2.1 billion |

| 20% | 24% | 427 million |

Silk Road TEUs by 2030 under two subsidy scenarios. Source: IED

But subsidies, while important, are not the only factor affecting Silk Road traffic levels. Others include transit time gains, routes via new Russia-China border crossings, standardisation and digitisation of consignment notes, and the launch of regular sea feeders from Japan and South Korea.

Ms Kozyreva said that experts’ economic forecasts currently vary widely because of the unprecedented geographic asynchrony of countries’ recoveries from the pandemic. IED’s best guess is continuation of past macroeconomic trends.

IED breaks down factors affecting Silk Road rail traffic growth to 2030 as follows.

| Possible change | Projected resulting change in annual TEUs (millions) to 2030 |

| 20% reduction of transport prices outside China | +632 |

| Reduction of transit time on the trans-Siberian routes to 7 days | +247 |

| New China-Russia border crossings and routes in the Far East | +74 |

| 100% use of the CIM/SMGS consignment note developed by European and Asian actors | +73 |

| Launch of regular feeders from Japan and South Korea | +51 |

| Acceleration of border crossings and of gauge-change procedures

Electronic data exchange between railways and customs; unified data exchange principles between railways |

+11 |

| Upgrade of border-crossing infrastructure in Poland | +6 |

| Construction of Rail Baltica’s 1435-mm line | 0, with no shifts among routes |

| Attainment of capacity limits at Polish border crossings | 0, but shifts among routes |

| Development of Baltic ports with launch of new short-sea feeder lines | -60 |

| Decrease of Chinese subsidies from 50% to 20% of transport costs | -442 |

Factors affecting annual change in TEUs. IED

Improvements or worsening of a factor on one route will shift traffic from or to other routes.

The IEC study found that Rail Baltica project to build a new north-south, 1435-mm railway through the Baltic countries may do little to attract or boost Silk Road traffic. Development of Baltic and Polish ports may even decrease it.

In the middle term, as the pandemic ends, IEC expects restoration of some supply chains and the emergence of new ones. In the long term, IEC sees rail’s share between Europe and Asia possibly rising from about 2% today to 5% for total transit and to 15% for central and eastern Europe, albeit under smaller total trade volumes than previously expected. Westbound traffic flows will continue to outweigh eastbound flows because they reflect trading in different commodities.

Silk Road gateways and routes

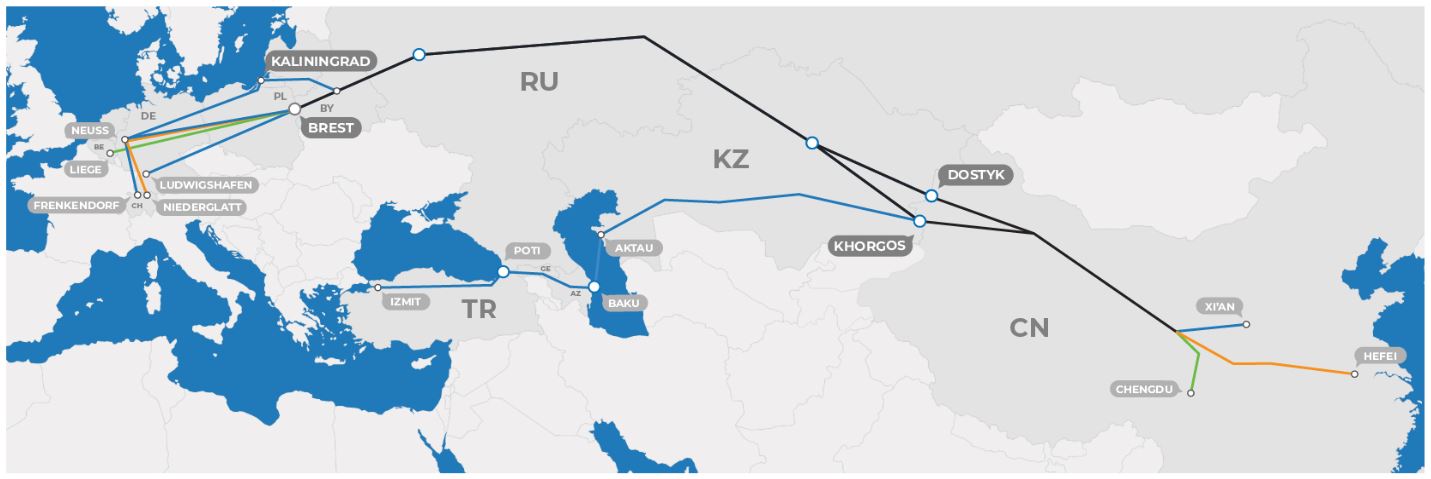

The conference also addressed the Silk Road’s various routes and their main gateways. Most trains still run via Brest/Małaszewicze. But other routes are emerging, including ones via Kaliningrad and short-sea ship to Hamburg or Mukran; the Middle Corridor south of Russia; and Poland’s 394-km broad-gauge line. New trains have been running to Paris and Vienna.

Brest/Małaszewicze

Wolfgang Rupf of RTSB said that the Silk Road’s growth has created problems, especially at the Brest/Małaszewicze border crossing. Despite work to increase capacity, it remains a bottleneck. But it has remained popular because it is still the fastest route and offers the most expertise. He said that the higher costs and inexperienced actors at other border points discourage the Chinese platforms who organise Silk Road rail services from using them except when Brest/Małaszewicze has exceptional problems.

Looking northeast at Kobylany, Poland, on 28 August 2020. The Bug River border crossing into Belarus and Brest are about 7 km ahead; Małaszewicze is just behind us. The tracks in the foreground and the yard are 1520 mm and the couplers Russian. The electrified tracks to the right are 1435 mm. Photo © Andreas Herold

Looking northeast at Kobylany, Poland, on 28 August 2020. The Bug River border crossing into Belarus and Brest are about 7 km ahead; Małaszewicze is just behind us. The tracks in the foreground and the yard are 1520 mm and the couplers Russian. The electrified tracks to the right are 1435 mm. Photo © Andreas Herold

Mr Rupf named all-rail routings north of Małaszewicze/Brest, including via Svislach, Grodno and Kaliningrad/Braniewo by rail to Duisburg and Neuss. He said that any route’s gateway terminal must organise reachstackers and customs inspection areas. Duisburg is a major destination for Silk Road trains. The number of slots in Duisburg is limited, Mr Rupf said, so changing the routing of Duisburg-bound trains does not help.

Kaliningrad

Mr Rupf said that RTSB is pleased with the growing services that bring containers by rail from China to the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, where chartered short-sea ships forward them to Hamburg. Three ships run in a circle. This allows a transit time from China to Hamburg of 12 days. Trains [reportedly of up to 1050 metres] cross the 1520-mm network all the way to the Kaliningrad port.

Problems in the system via Brest-Małaszewicze have been hurting transit time and thus client trust, Mr Rupf said. He hoped that Kaliningrad can relieve Małaszewicze and become the second more important routing for China-EU trains. Russia has a political interest this. Services via Kaliningrad are currently westbound only; an “additional product area” would be eastbound services.

Martin Koubek, Director Silk Road at intermodal operator Metrans, called Kaliningrad “very friendly” and said they help organise ad-hoc trains that customers may need. He pointed out that Hamburg offers Silk Road services [using trains or ships] a number of connecting intra-European rail services.

Routings of Silk Road trains operated by RTSB. RTSB

Routings of Silk Road trains operated by RTSB. RTSB

[George Raymond: Some Silk Road containers from Kaliningrad land at the German North Sea ports of Mukran and Rostock instead of Hamburg.]

Middle Corridor (TITR)

The Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) or Middle Corridor forwards a relatively small but growing number of containers from China by rail though Kazakhstan, by Caspian Sea ship to Azerbaijan and then by rail to Georgia. From Georgia, containers can continue either on rail via Turkey to the EU or on a Black Sea ship to the EU or Ukraine.

Mr Rupf of RTSB said that the TITR route involves a lot of water and customs regimes and for China is currently not an alternative to routes through Russia to reach the EU. However, Mr Rupf said, trains do currently run every 10 days from China via the Middle Corridor to İzmit, Turkey.

PKP LHS’s broad gauge from Ukraine to Sławków

PKP LHS manages the 1520-mm rail line that extends 394 km westward from Ukraine to a terminal in Sławków, Poland. This is the westernmost extremity of the broad-gauge network. (It is just slightly west of the Kaliningrad network, but much further south.)

Aleksandra Adamska of PKP LHS said that trains now run from Xi’an to Sławków. Mr Rupf of RTSB said that only westbound service is available, so Chinese subsidies must also cover the empty return trips. Ms Adamska said that Sławków is operating at 15% of its 300,000-TEU capacity, but volumes may grow because it is closer to Germany and Czechia than Brest/Małaszewicze and offers 1435/1520-mm transhipment deep within the EU, not at an external EU border. Today, customs checks occur at the Poland-Ukraine border, at the east end of the LHS line, but could be done at Sławków.

Unroofed box wagons westbound on the 1520-mm LHS line at Kozłów, Poland, some 335 km west of the Ukrainian border, on 15 October 2016. Note the Russian coupler. Photo © Keith Wilde, UK

Unroofed box wagons westbound on the 1520-mm LHS line at Kozłów, Poland, some 335 km west of the Ukrainian border, on 15 October 2016. Note the Russian coupler. Photo © Keith Wilde, UK

Ms Adamska said that LHS trains can weigh up to 5050 tonnes on axles weighing up to 24.5 tonnes. Trains up to 950 metres long can carry 48 to 52 forty-foot containers. In contrast, the EU is the midst of a long-term effort to accommodate 740-metre trains on its 1435-mm network.

The LHS line has no passenger trains and can run up to 12 freight-train pairs a day.

The 394-km PKP LHS line. LHS

The 394-km PKP LHS line. LHS

The Sławków hub offers 1435/1520-mm transhipment for containers and bulk goods, single-piece goods and dangerous goods, general-purpose tracks allowing side and end loading, warehouse space, a customs agency, and wagon and truck scales. Sławków and the PKP LHS line cater to traffic (1) between China and the EU and (2) between EU seaports and eastern Europe.

Ms Adamska said that regular trains now run between Xi’an, China, and Sławków, on a 9477-km route via Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine. Transit time could be as little as 12 days but have lately been up to 15-16 days due to congestion at the Sino-Kazakh border. Trains need 1.5 days to traverse Russia and 1.5 days through Ukraine. The Xi’an train brought supplies to fight Covid-19 to Milan in Italy in about 14 days. The service to Italy was for one customer, but could become a regular train. Despite tension between Russian and Ukraine in recent years, Ms Adamska said, traffic has never stopped.

She said that the PKP LHS route is working with TITR’s Middle Corridor route and called it useful for cargo that cannot go via Russia due to sanctions, for example. She said that PKP LHS was open for cooperation.

China services to Vienna and Paris

Yulia Kosolapova of Far East Land Bridge (FELB) said her company launched new routes from China to Vienna and Paris with special prices for personal protection equipment (PPE). FELB wants to make such spot trains into regular services.

Border crossings

Several speakers detailed the difficulties facing rail freight at border crossings. Their resolution is a major opportunity to increase rail freight’s efficiency in Europe and particularly Poland. Barriers include language, holding tracks that are too few and too short, and rules on the location of brakes tests and locomotive changes. One solution for a problematic border crossing can be an inter-governmental task force that engages all relevant parties and assigns tasks and deadlines.

An audience member recommended separating physical limitations at borders from those that exist only on paper.

The Frankfurt/Oder – Rzepin border zone

Roland Verbraak of GVT Intermodal said that the following improvements would facilitate trains on the 10-km section between Frankfurt/Oder in Germany and Rzepin in Poland:

- Locomotive changes and brake checks: Allow locomotive changes and brake checks at either station for trains in either direction.

- Language: Drop the requirement that drivers on the 10-km line be bilingual.

- Holding tracks: Use all available holding tracks in the area. Passenger trains should be on shorter tracks, freight on longer ones. Add tracks as needed.

Westbound near Zbąszyń, Poland, on 25 June 2018. The German border at Frankfurt/Oder is some 110 km ahead. Photo © Bob Avery

Westbound near Zbąszyń, Poland, on 25 June 2018. The German border at Frankfurt/Oder is some 110 km ahead. Photo © Bob Avery

A task force for solutions

Mr Verbraak described the task force on the Dutch-Germany border crossing at Bad Bentheim. He said that the Frankfurt/Oder – Rzepin crossing needs the same thing. It should include the involved countries’ ministries, rail network operators, train operators and intermodal operators. It should meet every three months and designate actions, action owners and deadlines. He asked whether the same idea could be applied at Brest/Małaszewicze.

What customers want in hubs

A brain-storming session among conference attendees identified qualities a hub needs in order to emerge and prosper, including:

- A clear focus on either on maritime or continental traffic.

- Location: central geographical location, but also vis-à-vis population and industry. Balance proximity to city and customers against availability of land for expansion.

- Good connections to main road and rail routes in all directions, including European rail freight corridors. Investment programme in progress to increase speed of all rail routes.

- Capacity: Optimised for originating, transit and arriving traffic. Long tracks. Ability to handle peak periods. Storage space for loading units.

- Technology: Process automation. Robust digital eco-system. Technology for carrying the 97% of European trailers that are non-cranable.

- Existing activities: Industry and logistic activities around the hub, including cross-docking and warehousing. Existing customer base.

A denser network of hubs gets trains closer to customer doors, shortens truck pickup/delivery runs and promotes resiliency.

This southbound Rail Polska train has just traversed Nowy Bieruń station – in the town of Bieruń Nowy – and now the Vistula River at 8:55 on the morning of 7 July 2018. Bieruń Nowy is between Katowice and Kraków in southern Poland. Photo © Derk Luijt

Hubs in Poland

Current main non-maritime hubs in Poland include Małaszewicze, Łódź and Poznań. Ms Pieriegud mentioned Poland’s proposed Central Railway Hub, which will connect new railway lines. But its planners made no presentation at the conference. Ms Pieriegud said that which lines will be built by 2030 is unknown.

PCC Intermodal’s Gliwice terminal is about 28 km west of Katowice in southern Poland. Two pairs of 650-metre loading tracks run along both sides of a wharf. The terminal handles no barges. Summer 2018. Photo © PCC Intermodal

What customers want in ports

Another central function of rail is to serve the hinterland of ports. A forwarder and the ports of Szczecin (Poland), Gdańsk, Hamburg and Rotterdam told conference attendees what they should look for in ports. But one customer had a complaint.

Three participants – Dominik Landa of DCT Gdańsk, Pawel Moskala of forwarder Real Logistics and Maciej Brzozowski of the port of Hamburg – mentioned criteria influencing customers’ choice of ports beyond the ubiquitous quest for cost-efficiency. Mr Landa emphasised paperless data exchange. Mr Moskala pointed to transit time for overseas trading partners like China, which requires “direct calls” of ships and trains. At first, he said, trains from China went to Hamburg even with containers for Poland. Customs clearance must also be efficient. Mr Brzozowski said that when choosing a port, customers also look at short-sea feeder connections, the visibility of major procedures, connectivity and the adaptability of IT systems.

In Poland: Gdańsk and Szczecin

Michal Jaworski of the Polish railway office said that in 2019, Polish ports handled some 8900 intermodal trains, of which only 1% served points outside of Poland. Rail’s growth was stable and continuous – until 2020.

Gdańsk

Dominik Landa of DCT Gdańsk said that DCT is the fasting growing terminal in Europe. It is the closest port to most final destinations in Poland. Rail’s hinterland modal share is 35%.

Just south of Gdańsk Główny station on 21 July 2016. The port of Gdańsk complex is out of the picture to the right. Photo © Mearten279

Dariusz Stefanski of PCC Intermodal complained about DCT Gdańsk’s handling fees for containers whose hinterland movement is by rail instead of road. No other North Sea port does this, he said. He said the fees contradict DCT’s praise of environmentally friendly intermodal transport.

Szczecin

Daniel Saar of German Railway (DB) called the port of Szczecin’s location, halfway between Hamburg and Gdańsk, ideal. The port is 68 km from the coast, which shortens truck runs. Its speciality is bulk cargo; it has the world’s biggest granite terminal. Mr Saar said that in 2019, the port had replaced Quebec as the world’s best bulk port. Customer expectations are rising, he said.

Rotterdam

Gilbert Bal of the port of Rotterdam said that in 2019, the port handled 7,423 container vessels, or about 20 a week, out of a total of 48 deep-sea calls per week. Deep-sea trade was greatest with Asia (up 6.5% from 2018), followed by South America and then North America.

The largest container ship was the 23,756-TEU MSC Gülsün. Compared to 2018, traffic grew as follows.

| 2019 | Change from 2018 | |

| Tonnes | 153 million | +2.5% |

| TEUs | 15 million | +2.1% |

| Container vessels handled | 7,423 | +3.8% |

Traffic growth reported by the Port of Rotterdam.

Containers were 81% dry, 14% reefer and 4% tank. They were 48% export and 52% import.

Transport between the port and its hinterland was 56% by truck, 33% by barge and 11% by rail. Some 38 rail operators and 21 rail traction providers serve the port. Operators of Rotterdam-Poland container trains include GVT, Hupac, Metrans, Optimodal/Kombiverkehr, P&O and PCC.

Rotterdam wants to raise the hinterland rail share to 30% by 2030. Mr Bal suggested that consumers may be willing to be pay a little for greenness and that this will work its way through the business models of industrial customers, freight forwarders and rail operators.

Intermodal operators

Presentations from intermodal operators included RTSB, whose focus is freight lines between Asia and Europe, and Metrans, which operates a growing network of hubs and trains in Germany, Poland and their neighbours to the south. The Silk Road is a major focus of both.

Rail Transportation Service Broker (RTSB)

Wolfgang Rupf of RSTB called it one of the leading rail operators on the Silk Road. The company is a 100% family-owned and neutral provider. They have two divisions:

- A block train division serving their customers, the so-called platforms located at the Chinese terminals from which Silk Road trains depart.

- A freight forwarding division to continue containers’ trips beyond Silk Road block train routes, for example from İzmit in Turkey to Europe.

RTSB runs their own block trains, including traction. This enables them to provide good estimated times of arrival (ETAs) and to react faster to problems and peaks.

In 2019, RTSB’s westbound block trains increased 8.3% to 1758 year-on-year, eastbound block trains 4.2% to 1210, and TEUs 2.5% to 393,774.

In 2020, on a year-on-year basis, RTSB operated 32% more block trains in the first quarter and 57% more in the first half.

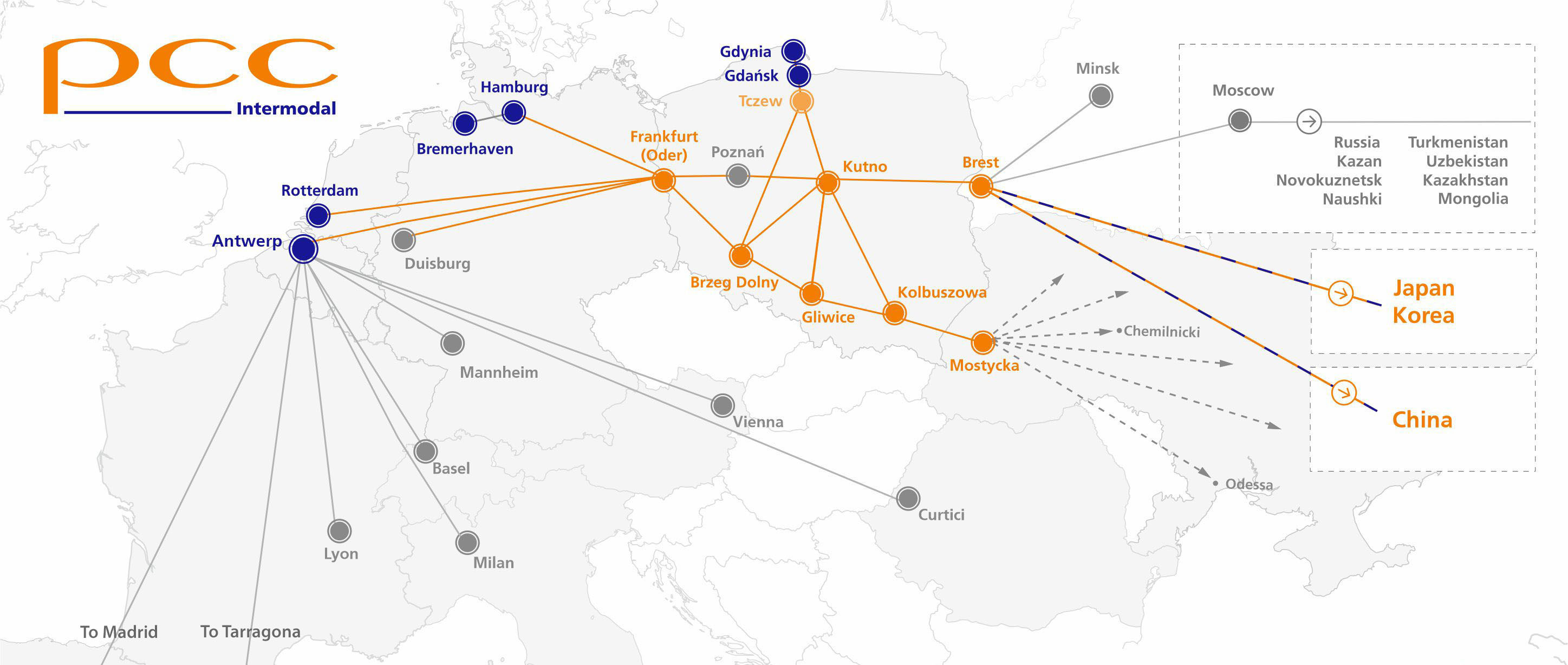

PCC Intermodal

PCC Intermodal

PCC Intermodal’s network extends to the border town of Mostyska (Мостиська in OpenRailwayMap), Ukraine. Partners provide connections to points south of Antwerp that include the border town of Curtici, Romania. According to a spokesperson, each week the company offers 24 connections to/from Gdansk/Gdynia, 10 to/from Rotterdam, five to/from Antwerp, Duisburg and Rotterdam, and three to five to/from Brest.

Metrans

Martin Koubek is responsible for Silk Road operations at Metrans, a subsidiary of Hamburger Hafen Logistic (HHLA). He said that Metrans is creating an intermodal network of five hub terminals and 12 end terminals in Austria, Czechia, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia.

Here are Metrans’ hub terminals.

| Country | Czechia | Czechia | Hungary | Poland | Slovakia |

| Terminal | Praha | Ceska Trebova | Budapest | Poznań (Gadki) | Dunajska Streda |

| Since | 1991 | 2013 | 2017 | 2011 | 1999 |

| Loading tracks | 13 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 9 |

| Shortest tracks (metres) | 6 x 350 | 2 x 500 | 1 x 750 | 4 x 550 | |

| Mid-length tracks (meters) | 2 x 550 | ||||

| Longest tracks (metres) | 7 x 600 | 6 x 740 | 6 x 650 | 3 x 630 | 5 x 650 |

| Portal cranes | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Reach stackers | 11 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 15 |

| Trains handled at same time | 10 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 9 |

Metrans data on its hub terminals.

These hubs all operate 24/7/365, Mr Koubek said, and connect to several ports by rail. Metrans runs 550 trains a week using 80 locomotives and 3,000 eighty-foot railcars. Daily trains between terminals make rail’s transit time comparable to trucks’. At each terminal, Metrans’ own truck fleet assures immediate last-mile delivery, he said.

Each week, 550 trains run on Metrans’ own lines. Service to the terminal at Gernsheim (Frankfurt/Main) began 1 September 2020. Metrans

Each week, 550 trains run on Metrans’ own lines. Service to the terminal at Gernsheim (Frankfurt/Main) began 1 September 2020. Metrans

In 2020, Mr Koubek said, Metrans has been trying to compensate for lower ocean cargo with more Silk Road rail traffic. The company’s hub-and-spoke system allows intra-European movement of Silk Road cargo by rail. Metrans trains connect with Silk Road trains at Hamburg, Brest/Małaszewicze, Kaliningrad and Dobra, Slovakia. These connections allow one Silk Road train to serve a number of destinations by rail.

Additional rail services linked with the Metrans network. Metrans

Additional rail services linked with the Metrans network. Metrans

Mr Koubek said that the efficiency of Metrans’ connections via hub terminals and the existing rail network will help keep Silk Road services viable even if Chinese subsidies drop. Metrans wants to continue growing its network to allow new routings and destinations. But fast and competitive rail requires the “real support” of European governments and the European Union, he said.

Metrans’ terminal in Pilsen (Plzeň), Czechia, on 21 September 2015. Photo © HHLA/Thies Rätzke

Technologies for rail freight and intermodal

The conference explored technologies for rail freight and intermodal, including help for train drivers learning new routes, digital freight services, hyperloop, hub technologies and transport of non-cranable trailers.

Ms Pieriegud of the Warsaw School of Economics pointed out that IT sometimes enables the rail system to avoid building physical infrastructure. And IT solutions are faster and easier compared to infrastructure projects.

Roland Verbraak of GVT Intermodal called for better technology to help train drivers learn alternative routes faster.

Kaspars Briškens of RailBaltica, the 1435-mm north-south rail line now being built through the Baltic states, said that the line’s digital freight services will include real-time tracking, surveillance and incident response, freight condition monitoring, data integration and, at terminals, gate automation, remote management and supervision, and autonomous vehicles.

Ms Pieriegud pointed out the huge costs of hyperloop technology for freight and lead times of way beyond 10 years. But Maciej Brzozowski said that the port of Hamburg is thinking about hyperloop for moving containers around the port.

Technologies for hubs

Harald Jony, CEO of WienCont, presented technology implemented at his trimodal terminal in Vienna.

Trains per week to and from the WienCont terminal in Vienna. WienCont

Trains per week to and from the WienCont terminal in Vienna. WienCont

Mr Jony said that long-term contracts with train operators and other partners have let the WienCont terminal establish electronic exchange and eliminate Excel sheets.

Trucks can check themselves in. Three years ago, the terminal implemented optical character readers (OCR) and infrared cameras to process both inbound and outbound trucks. They will implement these same checks for trains over the next two years.

Each department manager has a €10,000 budget for innovations, Mr Jony said. The terminal has two in-house developers. Paper is gone. Workers check containers with tablets. Smart glasses may replace tablets as soon as the glasses work better in bad weather and noisy conditions.

Entry/exit gates, reachstackers, cranes and tablets are connected in real time. Information flows between workers faster so they can prepare their work as early as possible. Mr Jony said that these innovations have speeded processing and allowed the number of trains to double.

Inbound trains average 51 minutes late, but WienCont works round the clock, so it can compensate. The terminal also handles some barges, from as far away as Rotterdam. Everything in the terminal is green. Electric reachstackers run on hydroelectric power only.

Moving non-cranable trailers

Intermodal hubs are more attractive if they can handle non-cranable truck trailers. Anna Sansanova of the manufacturer Lohr said that of the roughly 3 million trailers in Europe, about 100,000 or 3% have the reinforcement that allows cranes to load them vertically onto railway wagons. This percentage is even lower in Poland. Such reinforcement makes trailers costlier and heavier and thus lowers their freight capacity, Ms Sansanova said. Mr Jaworski of the Polish railway office said that among the intermodal loading units in Poland moving by rail, only 1.6% are truck trailers.

The articulated Lohr wagon carries two standard trailers.

Solutions being developed and implemented for the rail transport of non-cranable trailers include the CargoBeamer, Lohr, Nikrasa, R2L and Rola technologies. Lohr’s solution is an articulated wagon on three bogies with two pockets for trailers. To carry standard trailers 4 metres high at the corners, the Lohr wagon’s floor is just 22 cm above the rail, Ms Sansanova said.

The tray holding each trailer can pivot 30° for rapid horizontal un(loading).

To allow the rapid horizontal movement of trailers off and onto the pivoting trays of Lohr wagons, Lohr has designed matching handing equipment for terminals. Electric motors in this equipment rotate each wagon’s trays. Three photos: Lohr

Until mid-2020, five terminals had been equipped with the Lohr loading technology: Aiton, Calais and Le Boulou in France; Orbassano in Italy; and Bettembourg in Luxembourg. Lohr wagons now carry non-cranable trailers on four lines between these five terminals.

| Since | Line | Lohr wagons in service | Operator | Operator’s owner(s) |

| 2003 | Aiton (FR) – Orbassano (IT) |

35 | AFA | SNCF 50%, Trenitalia 50% |

| 2007 | Bettembourg (LU) – Le Boulou (FR) |

150 | Lorry Rail | SNCF 58%, CFL 33%, Lohr 8% |

| 2016 | Calais (FR)– Le Boulou (FR) |

105 | VIIA | SNCF |

| 2018 | Calais (FR) – Orbassano (IT) |

110 | VIIA | SNCF |

Terminals equipped with Lohr loading technology. Source: Lohr

Ms Sansanova said that these operators now have years of experience with commercial operation of the Lohr loading system in all kinds of weather.

Trains of Lohr wagons also serve three other French terminals: Macon, Lyon and Sète. Because these terminals lack Lohr handling equipment (at least for now), they only handle cranable trailers. But customers still benefit from faster, horizontal loading of these trailers at the Lohr-equipped terminal at the other end of the line. Lohr trains stop at the Macon terminal midway along the Calais – Le Boulou line. Sète and Lyon are the terminus of additional Lohr trains:

| Since | Line | Lohr wagons | Operator | Operator’s owner |

| 2016 | Calais (FR) – Sète (FR) |

25 | VIIA | SNCF |

| 2018 | Bettembourg (LU)– Lyon (FR) |

26 | CFL | CFL |

Lines serving terminals without Lohr loading technology. Source: Lohr

A sixth terminal with Lohr handling equipment will be the CLIP Group’s intermodal terminal in Swarzędz, 13 km east of Poznań, Ms Sansanova said. Loading stations for two Lohr wagons were completed in mid-2020. The terminal was to start handling non-cranable trailers in October 2020.

CLIP’s Swarzędz/Poznań terminal on 30 July 2019, looking east. A year later, handling stations for two Lohr wagons and thus four truck trailers would be completed at the far end of the lefthand tracks.

A Lohr wagon at its new handling station at the Swarzędz terminal on 13 July 2020. The wagon’s two trays have swivelled 30 degrees for quick, horizontal loading non-cranable (or cranable) trailers.

A Lohr wagon at its new handling station at the Swarzędz terminal on 13 July 2020. The wagon’s two trays have swivelled 30 degrees for quick, horizontal loading non-cranable (or cranable) trailers.

As demonstrated on 23 September 2020, reachstackers can service any of the Swarzędz terminal’s four 750-metre tracks. Three photos © CLIP Group

As demonstrated on 23 September 2020, reachstackers can service any of the Swarzędz terminal’s four 750-metre tracks. Three photos © CLIP Group

Trains of Lohr wagons carrying trailers from Poland and the Baltic region will run from Swarzędz/Poznań via the Bettembourg hub to France, Spain and Italy.

In blue, new lines equipped with Lohr wagons that will open in 2022-2023. Some terminals will offer Lohr handling equipment from the start; others may add this equipment later. Lohr

Network supported by Lohr technology. Lohr

Network supported by Lohr technology. Lohr

Ms Sansanova said that the Bettembourg and Swarzędz/Poznań hubs, equipped with Lohr equipment for horizontal loading and connected by trains of Lohr wagons, will support long-distance transport for trailers to/from London, Barcelona, France and Torino on the west and points in Poland on the east. As always, the trailers’ journeys will start and end by road.

Corridors

The conference looked at upgrades to the North Sea – Baltic corridor, the Rail Baltic line now under construction, the GUAM corridor and the vision of an Aegean-Baltic corridor.

TEN-T and the North Sea – Baltic corridor

Izabela Kaczmarzyk of T-Plan consultants presented ongoing efforts to upgrade the North Sea – Baltic Corridor (NSBC). It is part of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T). The NSBC comprises some 6000 km of rail routes, 4000 km of roads and, as far west as Germany, 2000 km of waterways. It connects markets in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland.

Meeting EU standards

The EU wants 83% of its TEN-T corridors to meet EU standards by 2030, including interoperable signalling and faster and longer freight trains. In Europe, 657 TEN-T projects worth €110 billion are in the pipeline, of which 237 projects were to be finished by the end of 2020 and 337 by 2030. Of these, 152 projects worth €39 billion aim to meet the EU’s TEN-T standards on clean fuels, bridge heights, 740-metre trains, terminal access, rail/port interfaces and 100 km/h speeds for freight trains. 53% are rail projects and 21% road.

NSBC rail projects

Along the NSBC, Ms Kaczmarzyk said, the TEN-T rail projects are worth €46 billion. Road is getting €39 billion, maritime €12 billion and inland waterways €5.6 billion. Multimodal projects account for €286 million, of which 10 are road-rail terminal projects worth €44 million for Berlin, Cologne, Duisburg, Hamburg, Hannover and Małaszewicze to be completed by 2030.

A major priority on the NSBC is efficient hinterland transport for ports, especially via rail and inland waterways. Planning must coordinate rail freight corridors, regions, cities and ports and consider alternative routes in case of blockages and major works.

Mostly for Germany and Poland

More than half of the NSBC’s 163 rail and 24 multimodal projects are in Germany or Poland, reflecting their share of the NSBC’s length. The biggest rail capacity problems are on the Polish network, which limits train length and speed and throughput at border crossings.

Along the NSBC, €1.5 billion has been budgeted for interoperable ERTMS signalling. While ERTMS has progressed in Belgium and Netherlands, it has lagged behind in Germany and Poland, where just 2% of the 947 km of NSBC lines have been equipped.

The EU is contributing 12.3% of NSBC project funding; the rest is from EU member States and other public funds. The source of 57% of the money is known. Private financing is scant.

Ms Kaczmarzyk said that implementing all the NSBC’s planned TEN-T projects would cut CO2 emissions by 10% in 2030.

Rail Baltica

Part of the plans for NSBC is the huge Rail Baltica project and its 870 route-km of greenfield railway infrastructure. Kaspars Briškens presented it. Rail Baltica’s main line will run south to north through Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia.

Interoperability to the south and east

The EU Green Deal seeks interoperability and sustainability, particularly for rail freight, Mr Briškens said. Rail Baltica’s track gauge will be the European standard 1435 mm. The main line will be double tracked. The project will make the Baltic states a crossroads between 1435-mm track and the 1520-mm network of the former Soviet zone, including the Baltic states.

The line will be equipped with EU-standard ERTMS signalling, electrified at 25 kV AC and designed for 249 km/h passenger and 120 km/h freights trains 1050 to 1500 metres long with 25-tonne axle loads. The line’s generous SE-C Swedish loading gauge will admit some project cargo, Mr Briškens said.

Terminals

Terminal development for Rail Baltica will focus in Lithuania on the existing terminals in Kaunus and Vilnuis, in Latvia on new terminals in Riga and Salaspils, and in Estonia on a new terminal in Soodevahe next to Tallinn and redevelopment of the port of Muuga. Mr Briškens said that unlike in western Europe, lots of extra land is available at the terminals. Private or smaller regional terminals may also be developed.

Services

Open access will be the rule for operators. Rail Baltica will foster shipment of 20-, 40- and 45-foot containers, bulk shipments, less-than-wagonload and LCL and innovative freight transport forms. For example, trains may offer connections to/from planes for ULD air freight containers and passenger baggage. Mr Briškens said that intermodal logistics will include opportunities for air freight integration, maritime integration, e-commerce logistics, value-added services such as customs and fuel delivery.

Linking markets

Rail Baltica expects a diversified mix of Baltic, north-south and east-west flows. Traffic is expected to/from Europe, Finland and the CIS, in equal parts. The project is expected to create new rail traffic flows on the eastern shore of the Baltic sea that connect to well-established flows on the east-west axis of the NSBC.

The line will link the established western European markets with emerging markets in north-eastern Europe and neighbouring Russia – from St. Petersburg south to Hungary, but also Ukraine, Belarus, south-eastern Europe and Turkey, Mr Briškens said.

Traffic to and from Finland is expected to be sizeable via the sea crossing or, perhaps in a more distant future, a rail tunnel. As Rail Baltica’s gateway to the rest of Europe, Poland is a critical link.

A new Silk Road route?

With its links with the existing 1520-mm network in the Baltic states and the rest of the ex-Soviet zone, Mr Briškens said that the new line is expected to become an additional and complementary route for the Eurasian land bridge crossing Russia and Silk Road trains from and to China. In presenting her company’s study, however, Ekaterina Kozyreva of IED International predicted that Rail Baltic will not divert Silk Road traffic from current routes.

Opening date

Construction of Rail Baltica has started. First operations are expected in 2027, followed by a few years of market adjustment.

The NSBC and Rail Baltica. Rail Baltica

The NSBC and Rail Baltica. Rail Baltica

The GUAM transport corridor

Altai Efendiev presented the GUAM transport corridor being promoted by Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova via the Kiev-based GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development. Mr Efendiev, the organisation’s secretary general, said that the corridor is seeking both better connections with Russia but also alternate east-west routes passing to the south of Russia. Such routes could lessen the GUAM countries’ dependence on Russia and strengthen their integration within Europe’s TEN-T.

Routes on the GUAM transport corridor being promoted by Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova. GAUM

Routes on the GUAM transport corridor being promoted by Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova. GAUM

Today, the most prominent east-west route running through this region is the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) or Middle Corridor, on which trains from China and Kazakhstan run (after crossing the Caspian Sea) through Azerbaijan and Georgia and sometimes (after crossing the Black Sea) Ukraine. Or vice versa in the other direction.

Mr Efendiev said that as the GUAM countries have turned toward the West, conflicts and territorial claims involving Russia have increased. He said that “we are sandwiched between two great powers”. The engagement from Russia is not very constructive and needs to be counterbalanced by engagement from Europe, he said. The GUAM group’s geography lets it both cooperate with Russia and offer alternative routes to the south of Russia. He called the GUAM corridor an attractive and viable alternative route for China-Europe-China freight.

GUAM member states are parties to the EU’s Eastern Partnership Program (EaP), whose focus is financial and technical support for transport. Poland is among the co-founders and champions of EaP, Mr Efendiev said. The EU wants to extend the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) to the east. The GUAM group has asked the EU for technical support for feasibility studies covering legal, normative, tariff/financial, infrastructure, environment, safety, security, technical, engineering, logistical and social issues. These studies will be the basis for inter-state agreements to implement the GUAM transit corridors.

GUAM’s big advantage as an inter-state framework is in the absence of conflicting interests among its member states, Mr Efendiev said. EU can use the GUAM “format” to promote regional cooperation, development, stability and security in the wider European space.

Mr Efendiev said that Chinese and European companies are interested in the emergence of the GUAM corridor over the next 10 years as a competitive alternative corridor. Austrian companies are already working with Azerbaijan, and Germany Railway (DB) with Ukraine.

Poland can serve as an example for Ukraine; the two countries have historical ties and are about the same size, Mr Efendiev said. He hoped that Poland will restore its interest in the GUAM platform, including regarding its potential vis-à-vis China and also Iran.

An Aegean–Baltic freight corridor?

Roumen Markov of the Bulgarian firm Large Infrastructure Projects presented his vision for an Aegean-Baltic multimodal freight corridor. He wants to get it onto the TEN-T map.

Roumen Markov’s sketch of his proposed Aegean-Baltic TEN-T corridor. It includes a new railway line (in red) and the Danube River (in blue). The 9.5 hours’ running time is for freight trains; passengers would travel even faster. [GR: the Danube’s source is Germany’s Black Forest, a bit further to the northeast than Mr Markov’s sketch shows. It is navigable as far west as Kelheim, between Nuremburg and Munich.] Large Infrastructure Projects

Roumen Markov’s sketch of his proposed Aegean-Baltic TEN-T corridor. It includes a new railway line (in red) and the Danube River (in blue). The 9.5 hours’ running time is for freight trains; passengers would travel even faster. [GR: the Danube’s source is Germany’s Black Forest, a bit further to the northeast than Mr Markov’s sketch shows. It is navigable as far west as Kelheim, between Nuremburg and Munich.] Large Infrastructure Projects

The Agean-Baltic Corridor (ABC+De) would combine sea, river, rail and road and the strengths of each, Mr Markov said. Its spine would be a new north-south rail line linking the Aegean and Baltic seas and greenfield ports at both ends. It also includes the Danube and its tributaries (De) and would manage problems linked to droughts, floods, navigation and the environment.

Mr Markov said that he has been working on the ABC+De project for eight years; it was triggered by the development of a steel plant in Bulgaria.

The new ABC+De railway would be called the South-North-Stream (SNS). Carrying both freight and passengers, the SNS would be a high-speed and high-capacity railway connecting the new ports on the Aegean and Baltic seas. It would be a short and fast route for goods between the Suez Canal and the Baltic region. The SNS line would allow night running of 1800-metre, 200 km/h freight trains of up to 11,000 tonnes on freight wagons of a new design capable of energy recovery and storage. They could link the Aegean and Baltic seas in 9.5 hours.

Of the Aegean-Baltic route’s 1,668 km, Mr Markov said, 583 would lie in Poland. Passenger trains would run at 400 km/h during the day and serve numerous stations in Poland, including the proposed Central Railway Hub.

The new rail line would connect greenfield ports at Vistula at the mouth of the Vistula River on the Baltic Sea and in the Ismara region on the Aegean Sea.

Port of Vistula

At its north end, the Aegeas-Baltic corridor would serve both the port of Gdańsk and a greenfield port at the mouth of the Vistula River, some 25 km to the southeast. Large Infrastructure Projects

At its north end, the Aegeas-Baltic corridor would serve both the port of Gdańsk and a greenfield port at the mouth of the Vistula River, some 25 km to the southeast. Large Infrastructure Projects

Port of Ismara

Mr Markov said that the new port in the Ismara region on the Aegean Sea would be as big as the largest northern European ports. Large Infrastructure Projects

Mr Markov said that the new port in the Ismara region on the Aegean Sea would be as big as the largest northern European ports. Large Infrastructure Projects

Mr Markov also calls the greenfield port in the Ismara region Maroneia. The map shows the Greek village of Maroneia, but the port’s location is not yet fixed. Google Maps

A deep-sea port with a draft of 25 metres, Ismara could handle ships up to 30,000 TEUs that cannot traverse the Bosporus. Its annual capacity would be 15 million TEUs. The current capacity of the Greek port of Piraeus is 6 million TEUs and that of Thessaloniki 1 million.

The Aegean-Baltic corridor’s SNS rail line would provide the missing north-south transport connection in eastern Europe, both facilitating transit traffic and generating freight along its route. The SNS would be a new route for goods from the Suez Canal through Greece, Bulgaria and Romania towards central and northern Europe, Mr Markov said. The rail line would also be a fast, green and economically efficient way for Polish business to reach the markets in southern Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. It would provide easy access to a new trade gateway on the Aegean Sea for the sale of Polish goods and make Poland a main player for freight in the Baltic Sea region and in eastern Europe.

The Aegean-Baltic rail freight corridor and the TEN-T. Large Infrastructure Projects

The Aegean-Baltic rail freight corridor and the TEN-T. Large Infrastructure Projects

The ABC+De project complies with the EU’s Green Deal, digitalisation and connectivity policies, Mr Markov said. He is asking the EU to integrate the Aegean-Baltic corridor within the TEN-T. But he said that the project’s main driver is a quest for economic efficiency that will spawn public-private partnerships (PPP) that finance and build the project.

George Raymond can be reached at graymond@railweb.ch.

© Copyright 2021 George Raymond. All rights reserved.

Back to Railweb Reports